The Curious Case of the Smelly Blob

- Nov 5, 2020

- 0 Comments

Free shipping on online orders over $1400 (contiguous US only).

In September, health officials in a Canadian town just outside Vancouver scrambled to explain a rare cluster of Legionnaires' disease cases in its business district. The problem wasn’t as much a case of why it happened as much as where.

They knew why.

Like most cities and towns around the world, New Westminster shut down in the wake of the pandemic. When businesses resumed, water systems that laid dormant for months suddenly had water flowing through them. That was a problem. Stagnant water in the pipes bred Legionnaires’ disease-causing bacteria, which was suddenly spreading everywhere. But which building – or buildings – was it? Inspectors zeroed in on those with cooling towers, air conditioning units, and decorative water features.

What is your plan when a city official, contractor, or engineer says a 1,000-gallon grease interceptor must be installed in your drive-through, parking lot, or another area where vehicles will be driving over it every day?

What is your plan when a city official, contractor, or engineer says a 1,000-gallon grease interceptor must be installed in your drive-through, parking lot, or another area where vehicles will be driving over it every day?

Trying to comply with local codes and regulations shouldn’t be difficult. You shouldn’t have to use all your resources to engineer, install, and maintain a grease trap. It should be easier and more affordable.

Commercial kitchen operators already know the benefits of using grease interceptors to capture used oil and grease -- cleaner sewage systems, reduced costs for wastewater treatment plants and fewer fines from municipalities.

Commercial kitchen operators already know the benefits of using grease interceptors to capture used oil and grease -- cleaner sewage systems, reduced costs for wastewater treatment plants and fewer fines from municipalities.

Plus, you can protect your facility's interior plumbing and make a little extra money selling used cooking oil to recyclers.

But did you know that by capturing all that grease you're also helping cut greenhouse gas emissions?

When it comes to disposing of food waste, which works best for commercial kitchens and our waterways – garbage disposals or strainers?

When it comes to disposing of food waste, which works best for commercial kitchens and our waterways – garbage disposals or strainers?

At first glance, a garbage disposal might seem like the easiest choice – just flip a switch and the food is gone. No scraps to throw away. What could be simpler? Plus, you keep waste out of the landfill.

However, food scraps that enter the wastewater treatment system can cause problems with our municipal sewer systems.

Grease interceptors have different weaknesses and points of failure depending on what they’re made of. Those materials affect how durable a particular grease trap is, and often affect how it’s designed. Design choices, in turn, also affect the reliability and durability of a grease trap.

Grease interceptors have different weaknesses and points of failure depending on what they’re made of. Those materials affect how durable a particular grease trap is, and often affect how it’s designed. Design choices, in turn, also affect the reliability and durability of a grease trap.

If concrete and fiberglass have problems, it seems as though it might make sense to use something stronger to construct the grease interceptor. Something like steel. But steel grease traps come with their own problems, and often have very short lifespans compared to other options.

Since concrete has so problems with corrosion, a substance such as fiberglass, which doesn’t have those problems, might seem to be a better choice. While fiberglass doesn’t experience the corrosion problems that steel and concrete grease traps do, it has some other challenges.

Fiberglass' rigidity and the use of other materials for inlet and outlet connections can create problems.

Grease traps – at least most grease traps – don’t last forever. Understanding why some fail might help keep your current interceptor running efficiently. If you’re in the market for a new grease interceptor, understanding why they fail might help you make a smarter choice.

Grease traps – at least most grease traps – don’t last forever. Understanding why some fail might help keep your current interceptor running efficiently. If you’re in the market for a new grease interceptor, understanding why they fail might help you make a smarter choice.

Today we take a look at why concrete grease traps fail.

Concrete grease traps are the oldest type of grease interceptor still in common use, but they have a number of inherent problems that lead to failure.

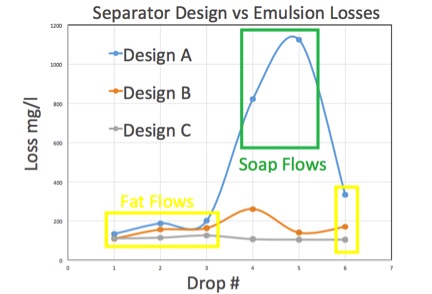

If you read our post on how emulsions can lead to fats, oil and grease (FOG) escaping a grease interceptor, you know that some grease will inevitably get into the wastewater system.

If you read our post on how emulsions can lead to fats, oil and grease (FOG) escaping a grease interceptor, you know that some grease will inevitably get into the wastewater system.

While the amount of grease getting through each day doesn’t seem that large, it constitutes what many feel is the greatest threat to the world’s sewer systems.

You might wonder why it would be a problem if the fats and oils have been emulsified — broken into tiny particles — through physical emulsion or, via soaps and detergents, chemical emulsion. And what that has to do with grease interceptor design.

© 2020 Thermaco Inc. All Rights Reserved / Privacy Policy

© 2020 Thermaco Inc. All Rights Reserved / Privacy Policy