How Narragansett Bay reaped the rewards of wastewater pretreatment

- Jul 21, 2015

The damage that grease and other pollutants can inflict on the environment is well documented, but few cases illustrate this as well as Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island.

Narragansett Bay is a prime example of what untreated sewage can do to the environment. However, it’s also a great case study in how pretreatment can help turn around polluted waterways and help reverse the impact of pollution.

A dirty beginning

The problem began in the 18th century. Rhode Islanders would empty their raw sewage directly into their nearby rivers that flowed into the bay. In the 1870s, the City of Providence perpetuated the problem with a newly constructed sewer system that collected untreated sewage, then dumped it into the city’s rivers and harbor through a series of outfalls.

In 1901, the city got serious about sewage and launched a treatment program. Interceptors collected sewage and pumped it to Field’s Point, on the west side of the Providence River, for treatment.

But the program was only effective for about nine years. The city’s exponential growth, combined with problems with the treatment process, led the city to dump large volumes of sludge directly into Narragansett Bay.

City officials knew that wasn’t sustainable, and began to research alternatives.

By the late 1950s, through a series of updates and the addition of new technologies to the Field’s Point plant, Providence had created an effective treatment program. But when the plant went without updates or maintenance work for almost two decades, progress stalled and pollution began to worsen.

A return to pollution

By the 1970s, nearly 65 million gallons of untreated sewage was flowing into Rhode Island’s waters each day. Grease deposits the size of soccer balls were sometimes seen floating in the bay. The bay’s shellfish beds, which had created a booming industry, were closed.

In 1979, seven years after Congress passed the Clean Water Act, the Environmental Protection Agency ordered the Providence to address the Field Point Plant problems. A task force was formed.

Solutions found

That task force, the Narragansett Bay Commission, drafted a plan for improvements at Field’s Point to satisfy EPA regulations. In 1980, voters passed a nearly $100 million bond to pay for the upgrade.

In addition to improvements to the treatment plants themselves, pretreatment regulations were enacted. Those regulations now include an extensive Grease Control Program implemented by the Commission.

The goal of the grease removal program is to limit the discharge of fats, oils and grease (FOGs) from food service establishments that tie into the municipal sewer lines. The less grease that gets into the sewer lines to start with, the less strain there is on the sewer system and the treatment plants.

The Narragansett Bay Commission issues Wastewater Discharge Permits to all food service facilities. From restaurants and resorts to nursing homes and hospitals, they’re all required to obtain permits to operate commercial kitchens.

To get the permit, facilities must install a grease interceptor that meets the commission’s criteria. They also must document all grease interceptor maintenance.

The commission has stringent requirements for the type of pretreatment devices required for a permit. There is a list of approved pretreatment devices and manufacturers. (Several Thermaco Big Dipper® models are included.)

The Narragansett Bay Commission has teamed up with the University of Rhode Island, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and EPA Region I to establish the Fats, Oils and Grease-Environmental Results Program.

The program combines compliance assistance, voluntary self-evaluation, inspections and certification. It helps the local food service industry get in compliance with pre-treatment rules and stay in compliance.

Through a combination of compliance assistance, voluntary self-evaluation, regulatory inspections and certification, the program has vastly improved the way local food service establishments manage grease. And, when restaurants chose to get certified under the program, it gets them one step closer to meeting the requirements needed for Rhode Island’s Hospitality Green Certification for the Hospitality & Tourism Industry.

A booming industry

In 1995, just 15 years after being designated as one of the worst treatment plants in the country, the EPA awarded Field’s Point the award for Best Large Secondary Treatment Facility in the nation.

Ongoing efforts to continue to improve the Field’s Point Wastewater Treatment Facility have led to the plant becoming a national leader in the use of sustainable energy for clean water.

Because of these efforts, the Narragansett Bay is now a focal point of Rhode Island tourism. Millions of tourists flock to the bay annually to swim, sail, boat, fish and kayak, and the shellfish beds once are an abundant source of local seafood.

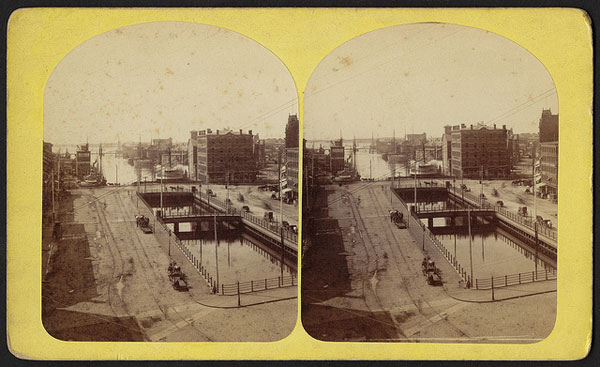

Top photo: Creative Commons licensed courtesy of Boston Public Library. Bottom photo: Creative Commons licensed courtesy of the U.S. Naval War College.